Dublin and the French Revolution

Maria Zukovs ‘wearing’ her research

Maddock Fellow Maria Zukovs looks at how the French Revolution was portrayed in the Dublin press.

In 1789, Dublin’s newspapers rushed to fill their pages with accounts of the unfolding events in France. Booksellers and printers capitalised on a market for French news which was built upon a pre-existing interest in French culture and long-standing trade between France and Ireland.

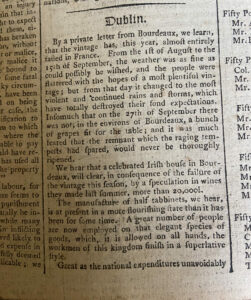

Excerpt from The Dublin Chronicle, October 1789 with mention of news from Bordeaux

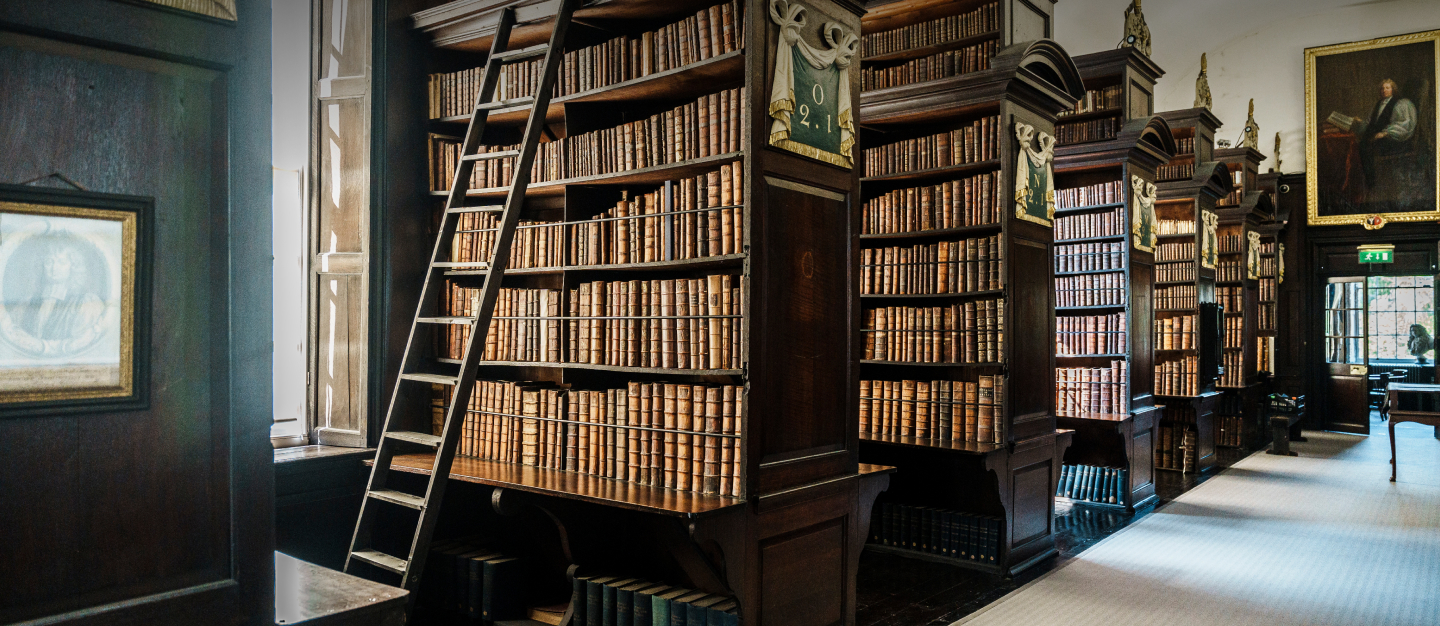

The research I undertook during my recent Maddock Fellowship allowed me to make considerable progress with my PhD project on Dublin press coverage of the French Revolution. I examined newspapers and periodicals as well as original editions of books and pamphlets, both printed in Dublin and imported from abroad. This material, much of which is from the Benjamin Iveagh collection owned by Marsh’s Library, shows that Dubliners were well connected to France and cared significantly about what was going on for reasons of politics, commerce and even entertainment.

An edition of The Dublin Chronicle from October 1789 contained news from Bordeaux regarding an Irish wine merchant who had speculated and lost £20,000 on the wine trade that year.

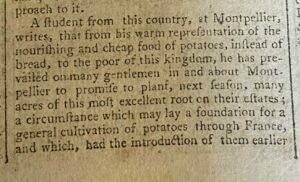

News from a letter from an Irish student in Montpellier, The Dublin Chronicle, December 1789

In a December 1789 edition of the same newspaper, I found a letter from an Irish seminary student in Montpellier, who wrote of his success in promoting the cultivation of potatoes among the locals, as a cheaper and more nourishing alternative to bread. Generations of Irish catholic priests were trained in the colleges set up in France, and the fate of these institutions was one of Dubliners’ many concerns in the early stages of the Revolution.

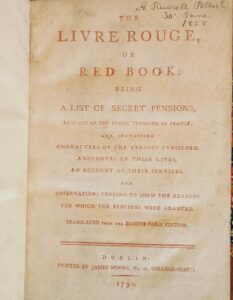

Numerous books were published in Dublin on French events, with many more imported. One intriguing book produced by the Dublin printer James Moore was an English-language edition of the Livre Rouge, a list of secret pensions paid by the French exchequer, that was printed entirely in red ink.

Title page for the Dublin edition of the Livre Rouge, printed entirely in red ink

Despite this fervour for the Revolution, many still wished to treat what was happening with sensitivity. A letter from Irish playwright William Preston to Dublin theatre manager Richard Dayley, regarding Preston’s play Democratic Rage; Or, Louis the Unfortunate, shows Preston’s concerns over ensuring that the material was treated with delicacy. Despite the play’s popularity in Dublin, Preston was unhappy with Dayley’s production and essentially forbid him from staging the play.

Through my fellowship, I have begun to bridge the gap between letter writing, newspapers and other forms of print. It has allowed me a glimpse into the lives of Dubliners experiencing the French Revolution in real time and to better understand how those events impacted their lives.

Maria Zukovs, PhD candidate, University of St Andrew’s