Gulliver’s Afterlives

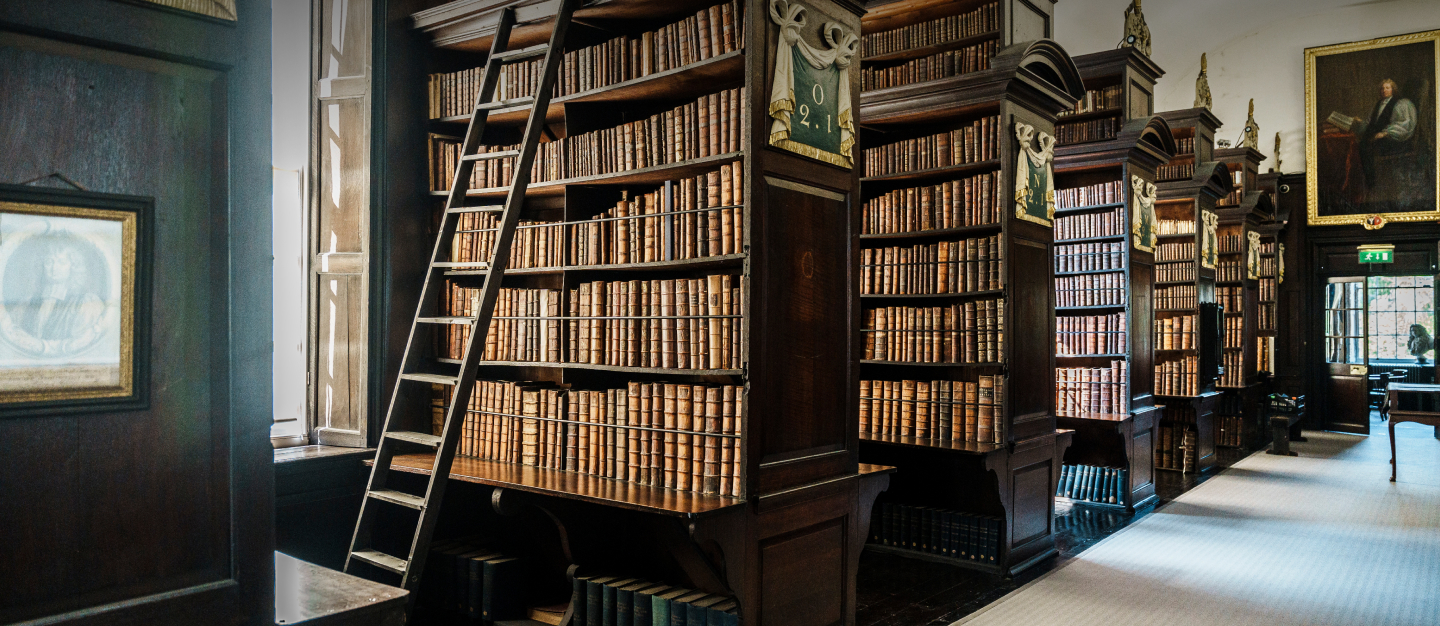

First edition of Gulliver’s Travels (London, 1726)

Daniel Cook explores our continuing fascination with Jonathan Swift’s satirical masterpiece.

As we inch towards the 300th anniversary of the first publication of Gulliver’s Travels in 2026, I have been thinking a lot about the global impact of that fantastical and terrifying masterpiece. ‘Lilliputian’, ‘Brobdingnagian’, ‘Yahoos’: our language remains steeped in Gulliverian lore. Since it was first published in 1726, there have been countless adaptations, translations and imitations of Dean Swift’s satirical fairy tale. The text itself has long been abridged, reworked, illustrated, and much more besides. An unlikely hero, Lemuel Gulliver has more recently appeared in Star Trek and Doctor Who, among many other pop culture franchises.

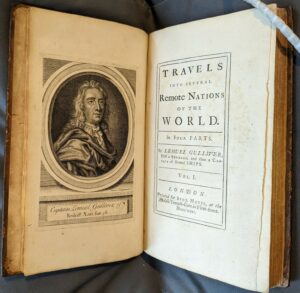

A German translation of the ‘New Gulliver’ (1731) a supposed sequel by Lemuel Gulliver

I have been working on book entitled Gulliver’s Afterlives, a cultural study of posthumous works attributed to or featuring Lemuel Gulliver. The global pandemic impacted my timeline with this project and I arrived to Marsh’s on a Maddock Research Fellowship with a book manuscript largely fully formed. A lot of Gulliveriana has been digitised, or can be acquired cheaply, much has been lost, miscatalogued, or simply ignored. But handling the items up close reveals important things easily missed, or that are simply unseeable, when viewed online.

During previous archival trips related to this project, including Oxford and Yale most recently, I found enough Gulliveriana to fill an imagined museum; but still I find new pieces. Marsh’s Library has a German translation of a putative French sequel (Le Nouveau Gulliver), and I stumbled across Gulliver’s Travels in an 1812 anthology by Henry Weber, Popular Romances. There, Lemuel sits alongside Robinson Crusoe and Peter Wilkins.

Above all, I am interested in the sorts of readers and viewers who have been consuming these types of books and images: Marsh’s Library affords a great opportunity to sit in their seat, as it were. The French and German translations found in the Benjamin Iveagh collection are ornate yet sturdy – clearly they were designed to be read and reread. The unofficial sequels, such as Voyage to Locuta (1818), are often cheaply or rashly printed. Some illustrated editions of Gulliver’s Travels are impossibly beautiful, seemingly tokens of a prestige piece of literature.

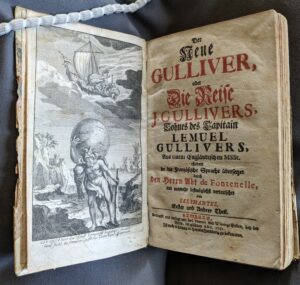

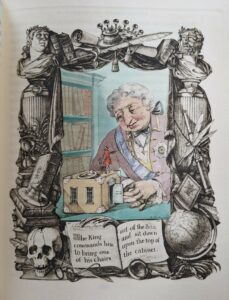

Gulliver in a Rex Whistler illustrated 1930s edition

In the Iveagh collection we find perhaps one of my favourite modern editions, a 1930 version replete with Rex Whistler’s busy but purposeful illustrations of the worlds in which the protagonist finds himself. Running a magnifying glass over his pages reveals so much astonishing attention to detail, much of which augments or overlays Swift’s original descriptions.

With a decent sense of the Gulliverian archive in mind, built up during Covid and other library visits, I could now focus on placing a palm-friendly 1797 French version alongside the definitive (and only slightly larger) edition of Gulliver’s Travels that appeared in the 1735 Works published in Dublin by George Faulkner. There’s also a copy of Motte’s 1726 London edition (there are more variations across copies of this version than you might think, so it’s always worth checking them closely). Then there’s the bicentennial edition produced by Harold Williams in 1926. Surrounding myself with these and other items brought me that bit closer to the world of Gulliver and his readers. But still the chase continues.

Dr Daniel Cook, Associate Dean for Education and Student Experience & Reader in English Literature, University of Dundee