Know your Adversary: Dissident Books in Edward Stillingfleet’s Collection

Maddock Fellow, Dr Ana Sáez Hidalgo explores books in Bishop Edward Stillingfleet’s collection written by his opponents.

Dr Ana Saez Hidalgo

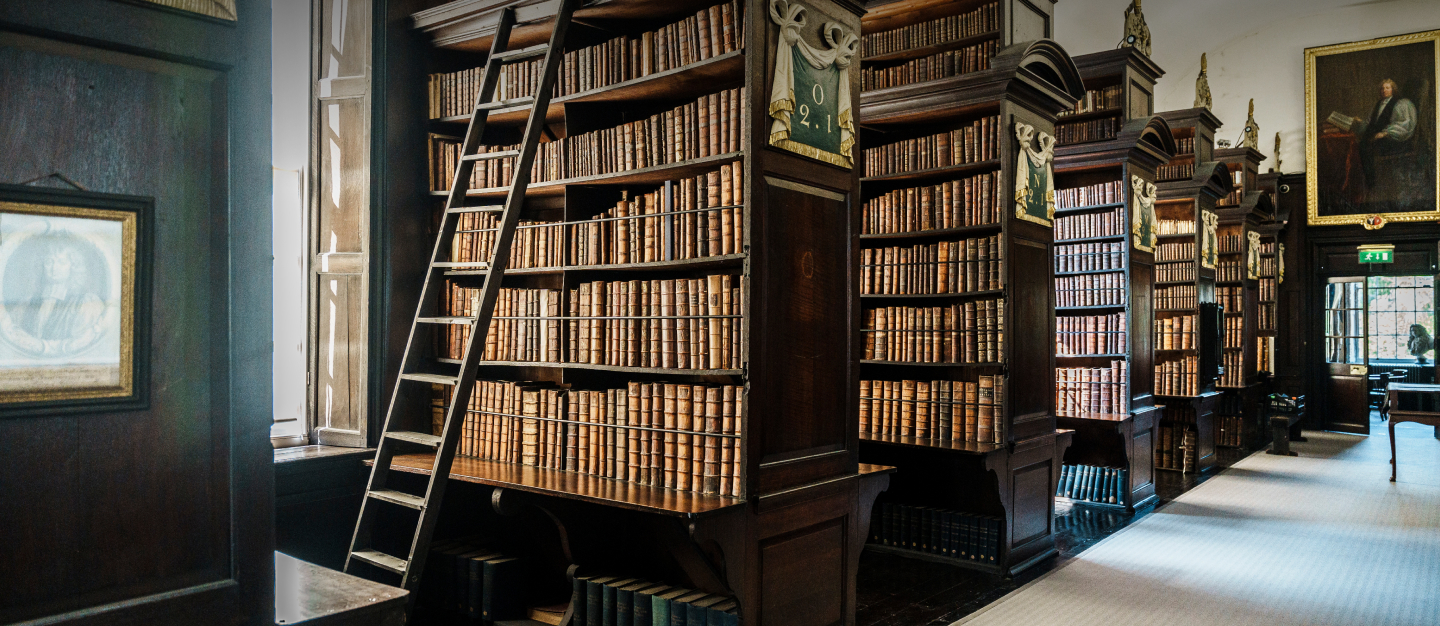

I recently spent two weeks in Marsh’s Library researching English Catholic dissidents who went abroad in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. This was a time of immense religious persecution as Protestants and Catholics vied for supremacy. A major purveyor of Protestant polemic at the time was Anglican Bishop of Worcester, Edward Stillingfleet (1635-99) whose 10,000 books are housed in Marsh’s.

Edward Stillingfleet

Stillingfleet engaged in extended and sometimes fierce exchanges with the writings of Catholics and other English dissenters. Enabled by my Maddock Fellowship (and encouraged by the extremely helpful Library staff), I searched Stillingfleet’s books for evidence of his reading—notes to himself in the margins, for example—and his views on the writings he opposed.

I quickly came to agree with Professor Crawford Gribben, a previous Maddock Fellow, about ‘Stillingfleet’s infuriating unwillingness to write in his books.’ Diligent, careful examination did turn up passages very faintly but incontrovertibly marked, as well as the rare comment—a word or two only, but in the bishop’s characteristic hand.

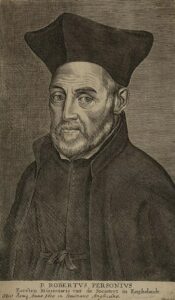

Robert Persons

The more I studied his library, the more I came to see how Stillingfleet’s collection reflects his engagement with Catholic texts. Clearly, he actively acquired copies of his adversaries’ writings, many of which must have cost him both effort and coin to obtain, given their Continental production and banning from sale in England. Many of these works are difficult if not near impossible to find outside of Marsh’s Library and give ample evidence of the wisdom of Narcissus Marsh’s wisdom in purchasing Stillingfleet’s library.

Notably relevant for my work were volumes such as Exomologesis (1653) by Serenus Cressy, a particular bête noire of Stillingfleet’s, as well as books by the leading figures of the so-called “English mission” – the mission to return England to the Catholic faith. Among these were numerous works by English Jesuit Robert Persons, including his politically-charged A Conference about the next succession to the crowne of Ingland (1594), in which the author proposes a Spanish (and Catholic) successor to Elizabeth I.

A succinct short title from ‘An answer to Mr. Cressy’s Epistle Apologetical’ (1675) By Edward Stillingfleet

Among the innumerable titles was also the first English translation of Teresa of Avila’s autobiography (1611), written by a Catholic—a surprising discovery! Pencil markings in its margins correspond to passages cited in Stillingfleet’s writings. Tempting as it is to attribute these markings to the bishop, more research is needed.

Finding such books intact at Marsh’s says much about the extraordinary value of Stillingfleet’s collection, but no less perhaps about the man. As his own fiery writings demonstrate, he rejected the ideas in his opponents’ books . Yet like a true scholar –and bibliophile– he not only acquired, but also retained the works of his adversaries for future reference.

Dr Ana Sáez Hidalgo, University of Valladolid, Maddock Fellow 2022-23